ICI Control Room - Northwich

A lot of the site's past infrastructure has been demolished in recent years. However, there are still remnants scattered around that make it worth exploring. One of these is a vintage control room.

We headed out early one frosty October morning and arrived on-site before dawn. After negotiating some razor wire and dense vegetation—a task made even harder in the pitch-black darkness—we were in. The control room is housed in a standalone building right in the middle of the site. To one side lies a completely barren wasteland offering no cover, and on the other, a hive of live operations buzzing with people and activity.

I had heard rumors that security in the past would hide in unsuspecting areas or place hidden cameras around the perimeter. Initially, I dismissed this as an exaggeration—until I spotted a trail camera hidden halfway up a tree as we crept along the edge of the site. We were about 10 meters away when I noticed it. Unsure if it had picked us up, we immediately stepped back and took a different route.

Proceeding cautiously, we couldn’t shake the thought that we might have triggered other hidden cameras on our way in. To play it safe, we left the area and waited in a remote spot to see if security would come to investigate. After a while, with no sign of anyone showing up and the sky beginning to lighten, we decided to push forward.

Hugging the tree line, we reached the derelict open area. The building we were aiming for was in sight, but getting there required crossing open ground with nowhere to hide if a patrol were to come by. We made a quick dash for it and reached another fence line. Following the fence for about 40 meters, we drew closer to the building. At the fence's end, we peeked around the corner and saw a few derelict buildings we could use for cover.

As we passed the first building however, a pickup truck suddenly came into view, parked parallel to our path. Unsure if it was occupied or if the driver had seen us, we quickly retreated back to the fence line. Dense bushes on the other side offered some cover. Just as we were getting ready to dive in, the truck's diesel engine roared to life, and it began moving.

We scrambled over the fence, landing in a patch of sharp brambles. Trying to stay as low as possible, we rolled around to try and bed ourselves in. Moments later, the truck passed us at a crawling pace. We hoped they wouldn’t notice the body-shaped imprints we’d left in the bushes. The truck continued its slow patrol, seemingly sweeping the entire site. We couldn’t tell if they’d spotted us earlier or if this was just a routine check.

We stayed hidden in the overgrowth for a while. By now, the sun was beginning to rise, and any cover provided by the darkness had disappeared. Our target building was still within sight, just a quick sprint away. This time, we moved cautiously, advancing only a few meters at a time and constantly scanning our surroundings.

In the distance, we could still hear the truck's engine. To our far left, I spotted another vehicle. Zooming in with my phone, I could just about make out "DOGS" written on the side—great, I thought, even more patrols. From my previous visit to the site, when I explored Mond House, I knew there was also a Vauxhall Corsa that patrolled the area. That made at least three vehicles actively moving around, possibly aware of our presence.

We weaved between empty shell buildings until we finally reached the control room. The external stairway had been partially chopped, and all accessible windows were sealed. After some searching, we found a way in. Inside, the stairwell led us to the main doors to the control room.

As we approached, the pickup truck pulled up outside the building. It lingered for a moment before circling around at a slow pace. At this point, paranoia set in; it felt like they knew we were here. Determined to make the most of our time, we entered the control room, ready to capture as much as possible in case we were forced to leave.

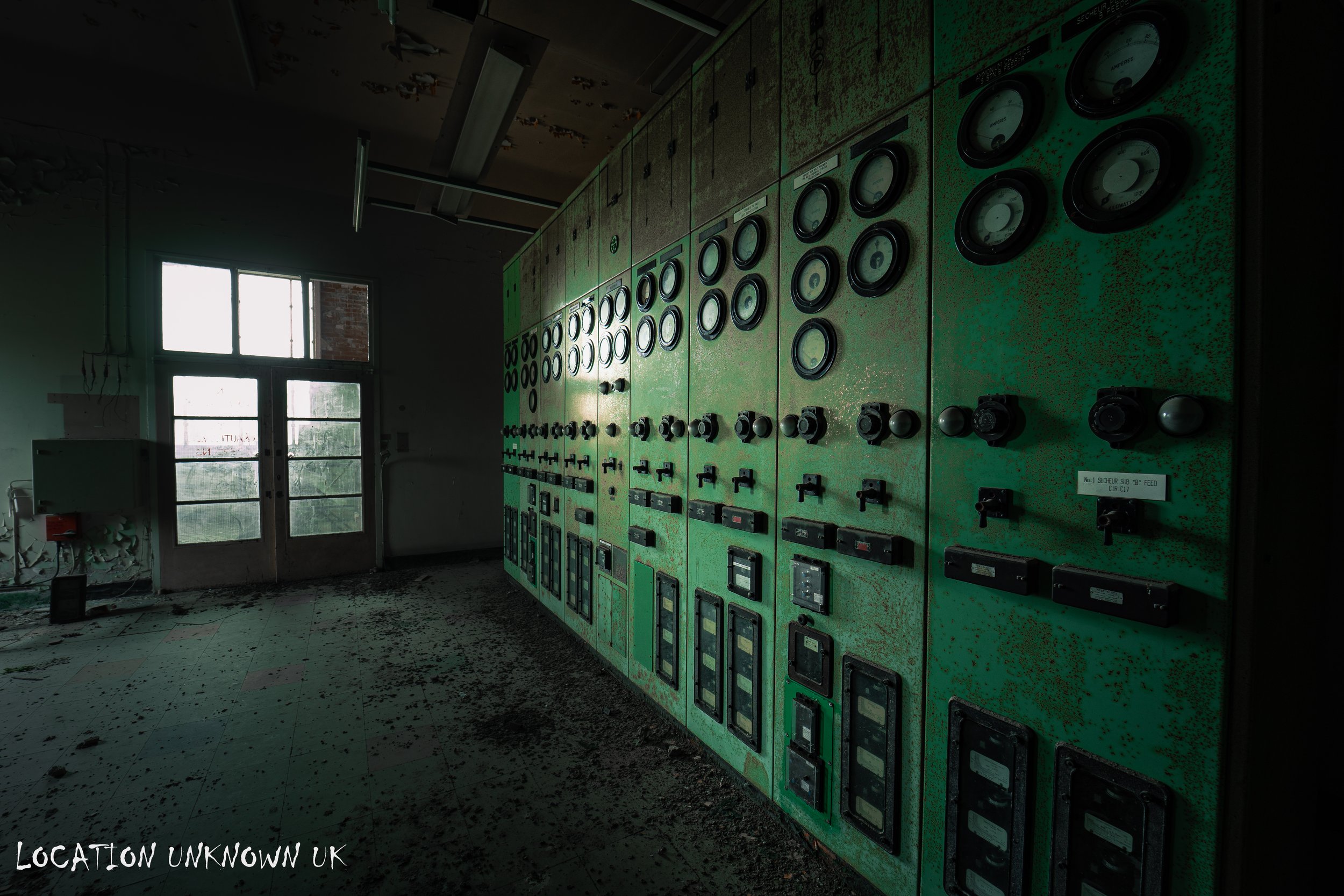

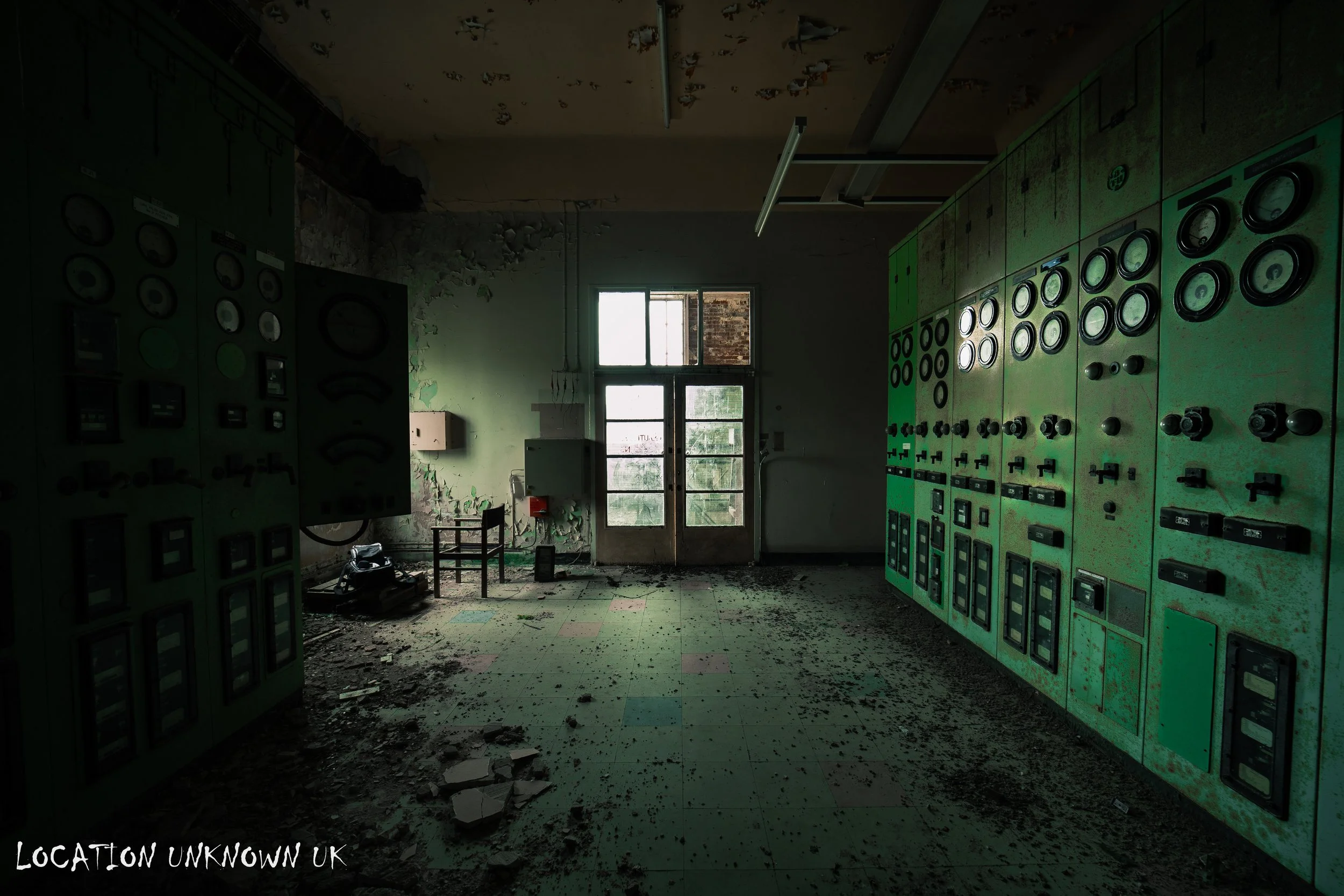

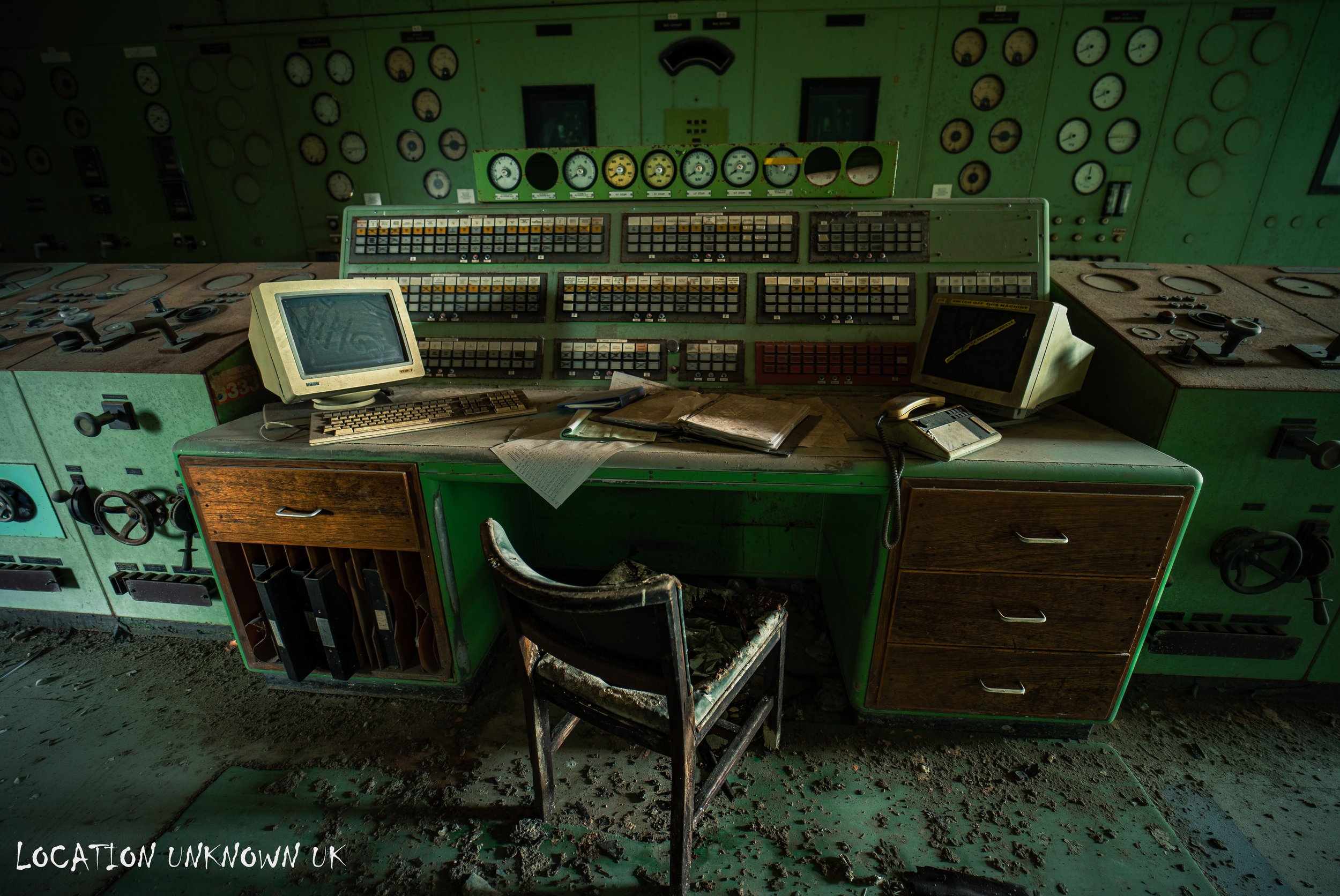

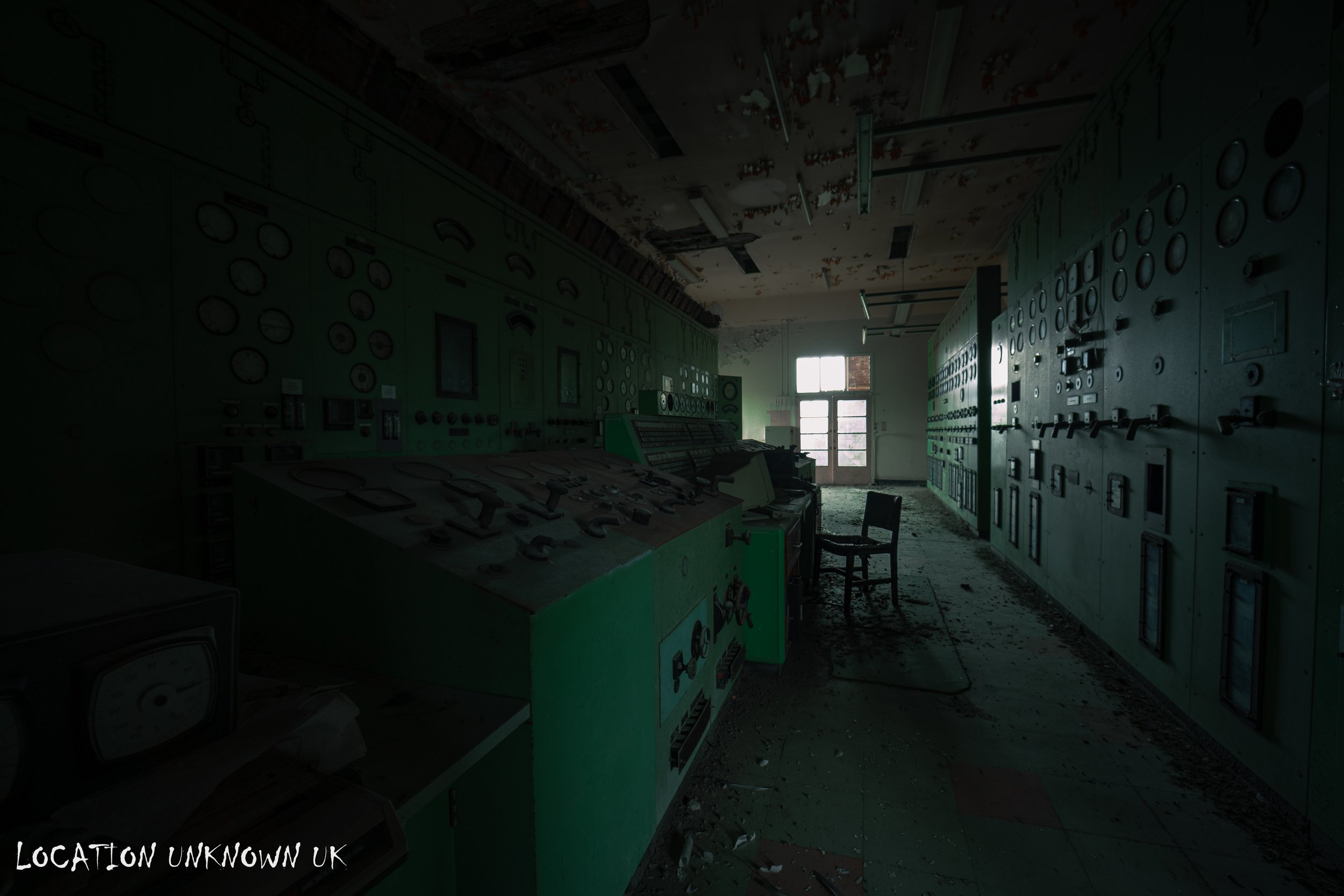

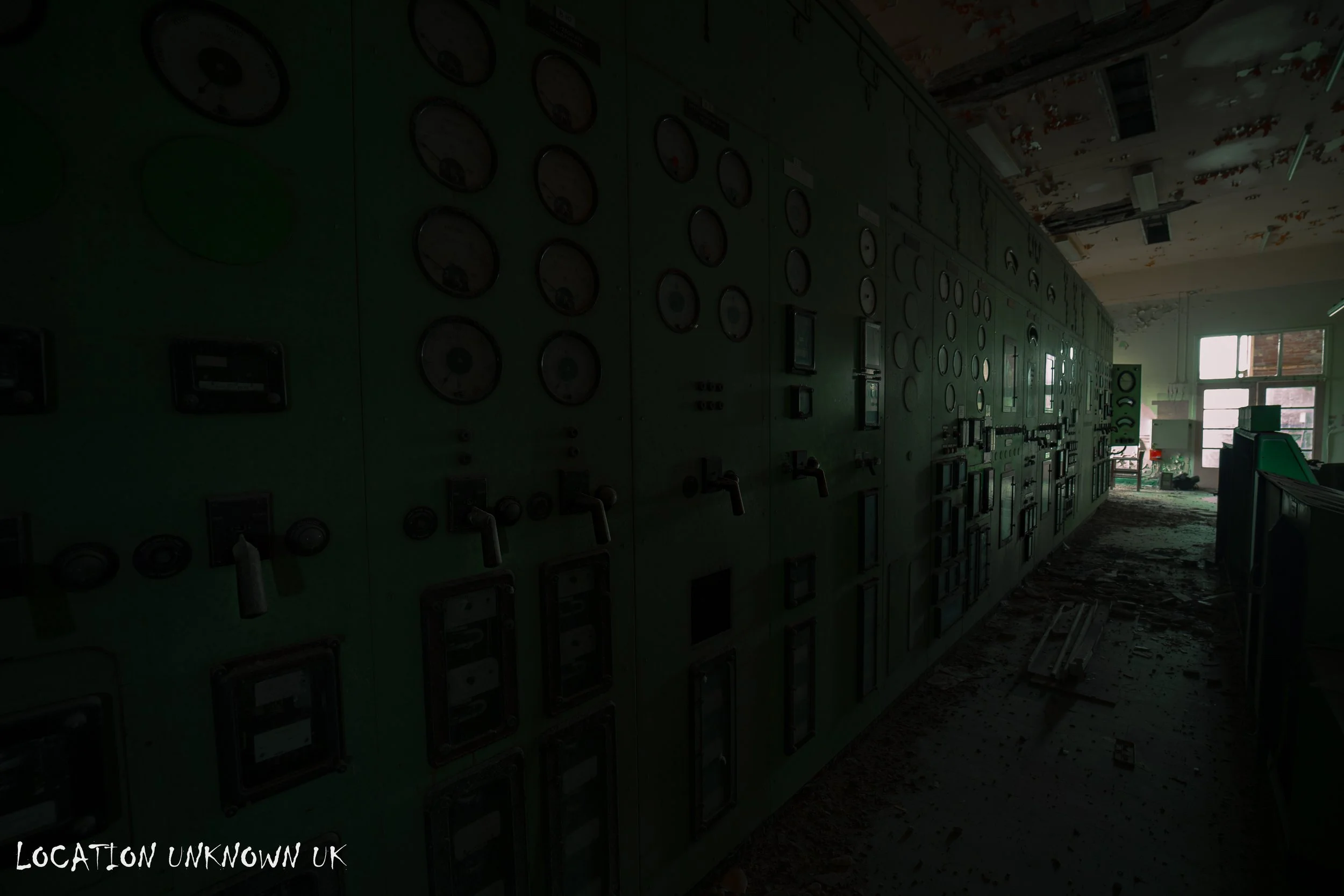

Thankfully, the doors were open, and we were in. The control room felt frozen in time. Dust blanketed the control panels, and an old 90’s windows PC sat on the desk, looking as though it might still power up if the place had electricity. The rest of the building was largely empty, aside from a door leading to another stairwell, which was screwed shut but led to nowhere significant.

The other buildings on the site, apart from the labs I had explored on a prior visit, were just empty shells. This control room was the main goal of our visit, and it did not disappoint.

After spending an hour or two inside, we decided it was time to leave. The dog unit vehicle had moved, and the pickup truck was still making its rounds in the distance. Were they still looking for us, or was it just a routine patrol? I guess we’ll never know.

History

“Winnington is home to the Brunner Mond UK chemical works, historically known for its production of soda ash. In 1933, during a high-pressure reaction experiment that didn’t go as planned, R.O. Gibson and E.W. Fawcett accidentally invented polythene—a material now widely used in plastic items such as bags. For much of the 20th century, most residents of Winnington were employed by ICI (Imperial Chemical Industries), although today, many work in the town center, with Brunner Mond still going albeit at a smaller scale. The houses near the ICI plant were originally built by the company to accommodate its workers. Winnington was also home to a combined heat and power station that supplied electricity to Brunner Mond. Although the power station was demolished in 2007, its vintage control room still remains. The origins of the chemical works date back to the 1860s when John Tomlinson Brunner, then an office manager at Hutchinson in Widnes, met Ludwig Mond, a chemist working at the same company. Mond envisioned a factory that would produce alkali using the ammonia-soda process, and Brunner joined him as a partner. Their Winnington factory opened in 1873 and eventually grew into Brunner Mond & Co. Ltd, the world’s largest producer of soda ash. In 1926, Brunner Mond merged with several other leading chemical companies to form Imperial Chemical Industries (ICI). The Winnington Works specialized in producing sodium carbonate (soda ash) and its derivatives, such as sodium bicarbonate and sodium sesquicarbonate. In 1991, the Winnington Works were divested to the re-established Brunner Mond company, which was later acquired by Tata in 2006 and rebranded as Tata Chemicals Europe in 2011. While production of soda ash and calcium chloride at the site ceased in February 2014, marking the end of 140 years of soda ash production in Northwich, the site’s head office and sodium bicarbonate production facility continue to operate in Winnington”.